Rec Letter: The Books That Help Us Write

The Yale Review editors share the books that have shaped how they think on the page

Earlier this week, we opened for general submissions (in case you missed it!), which got us thinking about the books that have most shaped our own writing lives. Most of us who work at The Yale Review are writers ourselves—poets, essayists, novelists, critics, historians. So when we asked some members of our editorial team to share a book that helped them with their own writing, we expected a wide-ranging list. Some of the books below offer models for argument or form. Others reveal what a sentence can hold, or what kind of logic a poem might follow. Each of them, for our writer-editors, grants a kind of permission.

This post includes a recommendation from a new member of The Yale Review’s editorial team: Clare Sestanovich, who joins us this fall as a senior editor and lecturer in English at Yale. And although not new to TYR, we’re glad to welcome Dan Fox—also a senior editor—as a lecturer at Yale, as well.

What are the books that helped you with your writing—or that always make you want to write? Let us know in the comments. And if you’re ready to share your own work, submit to The Yale Review before September 30—details here.

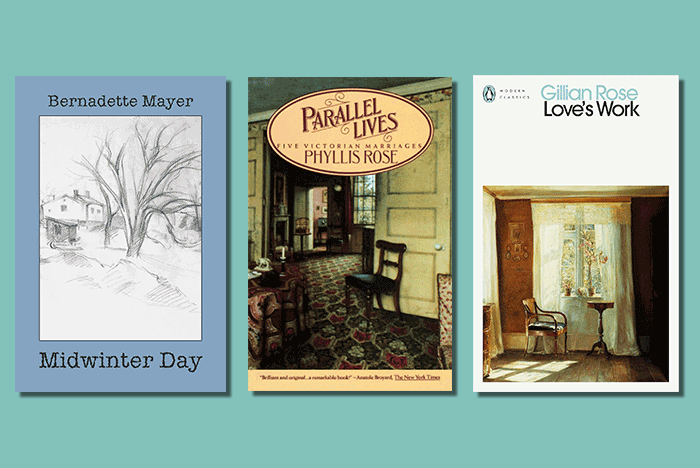

1. Love’s Work by Gillian Rose

I am always searching for books that combine feeling and thought, and this memoir by the British philosopher, written as she was dying of cancer, is exemplary in both. I can be too sentimental in my writing (or at least my first drafts; I have great editors) and this book sets a high bar for the thought feeling or felt thought I am often attempting to capture. —Joanna Biggs, deputy editor

2. Parallel Lives: Five Victorian Marriages by Phyllis Rose

This is a brilliant, absorbing group biography of some 19th-century British writers and their spouses, and endlessly instructive for writers of researched nonfiction. Most valuable for me was Rose's handling of other scholarship, which she treats as a species of gossip. Her sentences fold the posthumous dramas of research and criticism—of discovering and debating what can be said with confidence about the dead—into the social and intellectual dramas which preoccupied these figures while they were alive. Was Harriet Taylor and John Stuart Mill's marriage consummated? Did George Eliot and George Henry Lewes make a virtue of being ostracized? People wanted to know, and still do. —Sam Huber, senior editor

3. Madness, Rack, and Honey: Collected Lectures by Mary Ruefle

In the course of a history of science dissertation that had become as much about literary analysis as scientific practice, I struggled to write about writing. I remember sitting on a train—I think it was to DC but it might have been New York—and reading Mary Ruefle’s essays just for fun. They were rigorously thoughtful but also open-ended. They were lucidly written. They were energizing. I realized, sitting on that train, that if I was going to talk about the poetics of scientific writing, it would be perfectly acceptable to borrow writing techniques from a poet-essayist. The way Ruefle wrote about the work of metaphor seemed to speak directly to the ambivalent morality of the science I was studying, and to the scientists’ own grappling with that ambivalence. Ruefle modeled a mode of argumentation that leaned into polyvalence without sacrificing clarity. She helped me develop a new, essayistic voice. Mary Ruefle is the reason I finished my dissertation. —Caitlin Kossmann, editorial assistant

4. Midwinter Day by Bernadette Mayer

This is a book I come back to again and again for its sweep and scope, its offhand genius, its placement of political and literary history right up against lewd dreaming and domestic parental life. Each time I rediscover it, this epic poem feels both more ambitious and more permission-granting than the last. —Maggie Millner, senior editor

5. Souvenir by Michael Bracewell

I believe every writer should attempt a description of a picture or a piece of music once a week. Not easy, but superb calisthenics. When I need to remind myself how it’s done properly I open Souvenir by the British critic and novelist Michael Bracewell. Barely a hundred pages long, described as “a eulogy for London of the late 1970s and early ‘80s,” Souvenir is a memoir that eludes the first person, a marvel of brevity and ekphrasis that teaches me how to look at and listen to the city. Bracewell suffuses songs with the specific feeling of walking through London in spring or sitting on a commuter train in winter. He spots tectonic cultural shifts in the cut of a suit, prophetic intimations about art and money in the design of a West End bistro. I return to this book every year and, like all my favorite works of art, it outruns my capacity to describe what it does to me. —Dan Fox, senior editor

6. Minima Moralia: Reflections from Damaged Life by Theodor Adorno

Negativity gets a bad rap in this country. The wrong attitude can get you a long way if you do it right; it keeps you thinking that things, no matter how good or bad, can always be otherwise. The popular impression of Adorno is of a top-tier, world-historical crank—his pronouncements on modern social phenomena, delivered with unwavering confidence, are as likely to enrage as edify—but the German-Jewish philosopher of music, history, and the catastrophe of modernity was hardly cantankerous for its own sake. When a supposedly rational, democratic society gave itself over to reactionary nihilism and reality-shattering violence, Adorno found in negativity—as well as irony, its charming cousin—a kaleidoscope for reimagining the world. Minima Moralia is comprised of 153 fragments and short essays on a dizzying range of subjects, which Adorno wrote in exile in England and the US during the war which destroyed tens of millions of lives as well as a culture that, because of (not despite) its awe-inspiring achievements, was always headed that way. Yet for Adorno, to focus on how the everyday reflects this calamity was not just to pour the baby enthusiastically out with the bathwater, but to demonstrate how the very fact of being able to witness the world and discuss it critically is evidence of the possibility—and maybe only that—of redemption. I started really reading Adorno only in the last few years, and, though I have problems with much of what he says, and even with his methods, in our late hour I find his sang-froid and willingness to interrogate even his own attachments not only bracing, but genuinely uplifting. Reading Adorno reminds me that to write is to insist on one's right to be intelligent, to refuse the bullshit, to live well. —Jack Hanson, associate editor

7. Negative Blue: Selected Later Poems by Charles Wright

Lately, when I start to feel stuck, or sense I’ve overworked a poem, or that I’m trying to force meaning, I flip open to a page of this edition of selected poems by Charles Wright. His poems move loosely by observation, meditation, and speculation, with sly wit and offhand wisdom, and I’m reminded just how much a poem can contain. They form their own landscapes, but the literal landscape they often evoke is Virginia, where I’m from, and I like how strange, or strangely familiar, it becomes in his hands. —Will Frazier, digital director

8. Peaces by Helen Oyeyemi

Helen Oyeyemi is my favorite living novelist because her work so totally reimagines the tie between density and genius. She pulls off the impossible: books that go down breezy and then gut-punch you with their brilliance. Right now I'm reading Peaces, which, in true Oyeyemi fashion, refuses to issue a divide between the fanciful and the literal. The book makes me reconsider the kinds of thought fiction enables, and it's pushing me to experiment with the conceptual space between the “as” of simile and the equations of metaphor in my own fiction. —Lacey Jones, associate editor

9. Why Did I Ever by Mary Robison

My first copy of Why Did I Ever was a loan from a classmate. We were in the same writing workshop, which seems fitting, because most writing workshops would have no idea what to do with this book. Comprised of 536 fragments—some as short as a sentence, none longer than a page—Why Did I Ever tells the story of a woman named Money, a struggling script doctor whose problems in work and life (and money!) have no easy diagnosis, much less any obvious treatment. Here the workshop would pause to question whether “story” is quite the right word: readers, like Money herself, may find themselves adrift in a narrative that flits from one non-scene to another, that never bothers to introduce characters, that starts every conversation in its middle. But who cares! Or rather, it’s exactly why I care, and why I’ve returned to this book so many times. Robison invents a form that captures—beautifully, hilariously, often tragically—what it feels like to inhabit a life that doesn’t develop the way a plot should, a mind that makes its own rules. In the years since I first borrowed Why Did I Ever, I’ve bought my own copy—two, actually, so that now I can be the one to loan it out. —Clare Sestanovich, senior editor

This has such different recs! I don’t think I’ve seen very many people talking about these books!

New short story https://nimnim1.substack.com/p/poly-hell