Notes on Note-Taking

Joanna Biggs reflects on Joan Didion’s notes—and offers a prompt for your own

As we approach the dog days of summer, we at The Yale Review are all about to hit pause for the coming few weeks as our team travels, rests, and regathers before the fall. Before we go, we’re sharing some thoughts from our deputy editor, Joanna Biggs, about note-taking—how it can be a way of listening, of writing, of living. It comes with a prompt for your notebook, which you can try wherever you find yourself in these final weeks of summer.

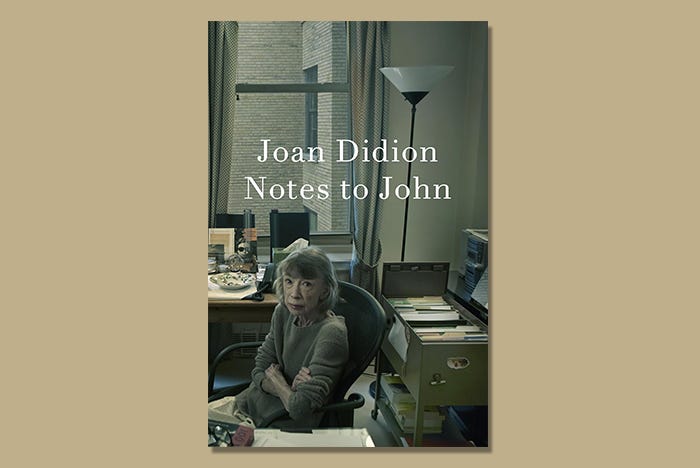

When Joan Didion’s Notes to John were published earlier this year, many critics wondered aloud if they ought to have been. Loose leaves found in a folder on her desk after she died, the new book was in fact post-therapy notes written during a critical time for Didion’s family between 1999 and 2003. Would Didion have liked us to see her so rawly? Is it wrong to publish someone’s notes, by definition unfinished, and personal ones at that? But when I read the book, I liked the notes so much more for being unrefined. We have plenty of Didion Refined! Here’s an exchange she captures from a therapy session on December 13, 2000, which is also about not being perfect:

“Most people do make accommodations. You look at this from a very special point of view. You have an unusual purity of intention. You’re extremely intelligent, absolutely logical. You demand that everyone else live up to this standard.”

I said I didn’t live up to it myself.

“Always being right doesn’t necessarily make you feel good about yourself.”

I said I supposed he was saying that I wasn’t always right.

The Didion hallmarks are there: the deadpan tone, the tart precision, the mild skepticism. But a question comes to mind: How did she remember what her therapist, Roger MacKinnon, said well enough to capture a whole thought, and the words in which he expressed the thought? Throughout Notes to John, Didion keeps her speech reported, while quoting MacKinnon’s words. But her training as a reporter was in a time of Dictaphones and spiral notebooks, remembering and listening, and this time the reporting was personal: her daughter’s drinking had gotten out of control, and she had come to analysis at her request. She was keeping the notes for her husband, so that he could go to therapy without going to therapy, as it were. (John went once or twice with Didion, but otherwise didn’t.) She may also have had a book in mind; she might have been one of those people—not uncommon in writers—who doesn’t know what she thinks unless she writes it.

I felt I knew Didion better from reading her notes; I felt there was more of her there. And it got me thinking about notes as a form of their own. A friend told me that one of the important parts of training to be a therapist is writing down what happened after each session, putting the spoken into words as a prompt to listen well in the session itself. Note-taking was listening. I remembered the moment in Lydia Davis’s essay on note-taking when she showed how her daily writing in subway cars often formed the basis of a story or essay. Note-taking was writing. I remembered Garth Greenwell, Lena Dunham, and Brandon Taylor’s Substack posts about their note-taking systems. Note-taking was thinking. I remembered Mary Wollstonecraft’s Hints for a second volume of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman. Note-taking was the tip of a new book.

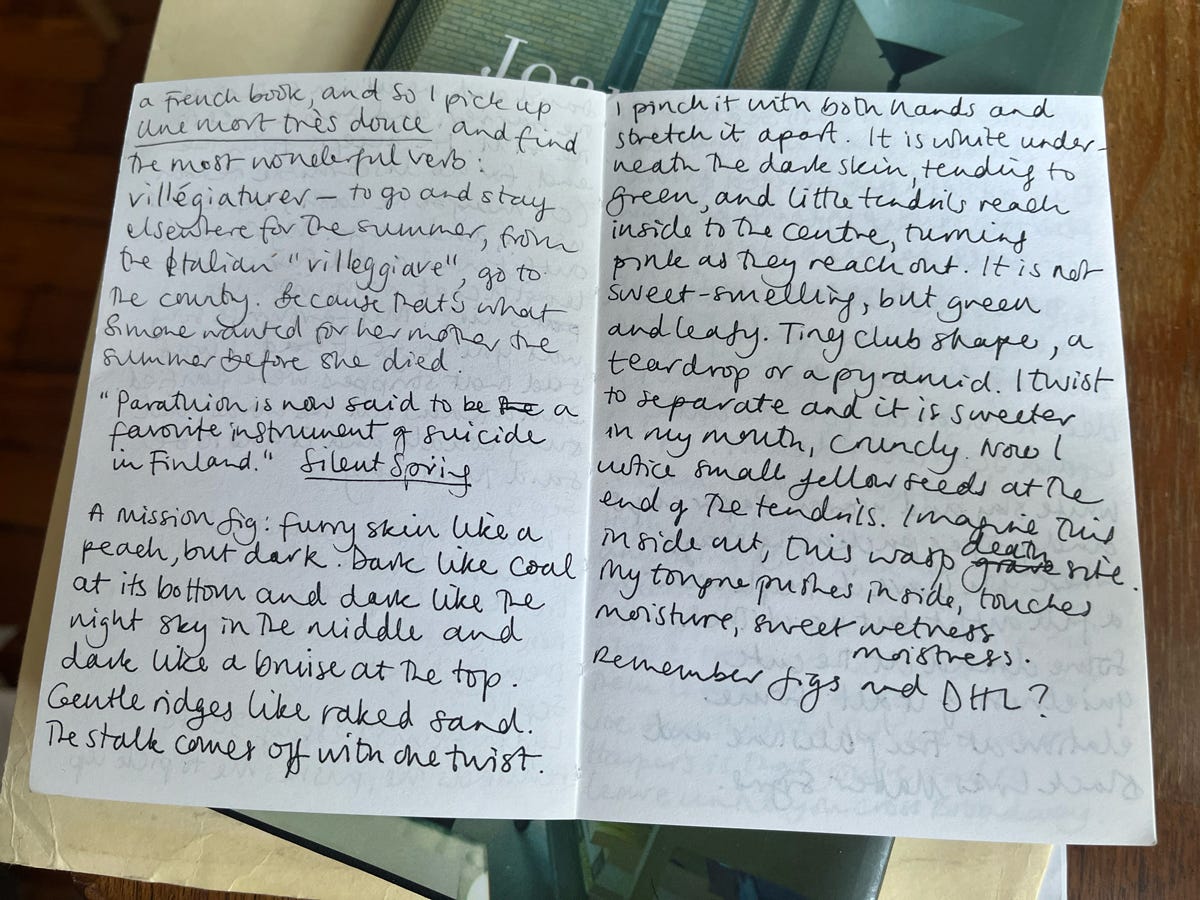

I remembered that I had a burst of note-taking last summer, and dug out my half-finished notebook. (OK, quarter-finished.) I’d been spurred by Davis’s essay, which is concrete about what sort of note-taking is helpful to a writer. I’d taken notes at a show at the Whitney Museum in New York City, during an early morning at the beach while my boyfriend surfed, on eating a tiny dark fig. I’d written quotations from my reading, and things my friends said that I wanted to remember. But I hadn’t tried to write down a conversation, not once. And I wondered why.

Was it too hard? Would it invade the privacy of the people I loved? Would I find it horrible to write down the stupid things I had said? Would it be too gauche to take out a notebook as I chatted with friends? Was I unable to listen closely enough to do it, always distracted by my own thoughts?

So I thought I would challenge myself to take notes on a conversation this summer, like Didion. I can leave myself out of quotation marks, as she does, and listen to what is being said, whatever it is. My first attempts might be brief and messy, as they should be. And instead of the airlessness of journaling, the mind pivoting around itself once more, I might be able to understand myself differently in the improvisation of a conversation. Join me?

—Joanna Biggs, Deputy Editor

Prompt No. 2: Notes on a Conversation

Sometime in the next few weeks, take notes on a single conversation—not after the fact, but in the moment or just after. Keep yourself outside the quotation marks. Don’t worry about mess or gaps. Just try to catch what was really said, as best you can. Then put the notebook away until later in the fall. See what you find when you return to it.

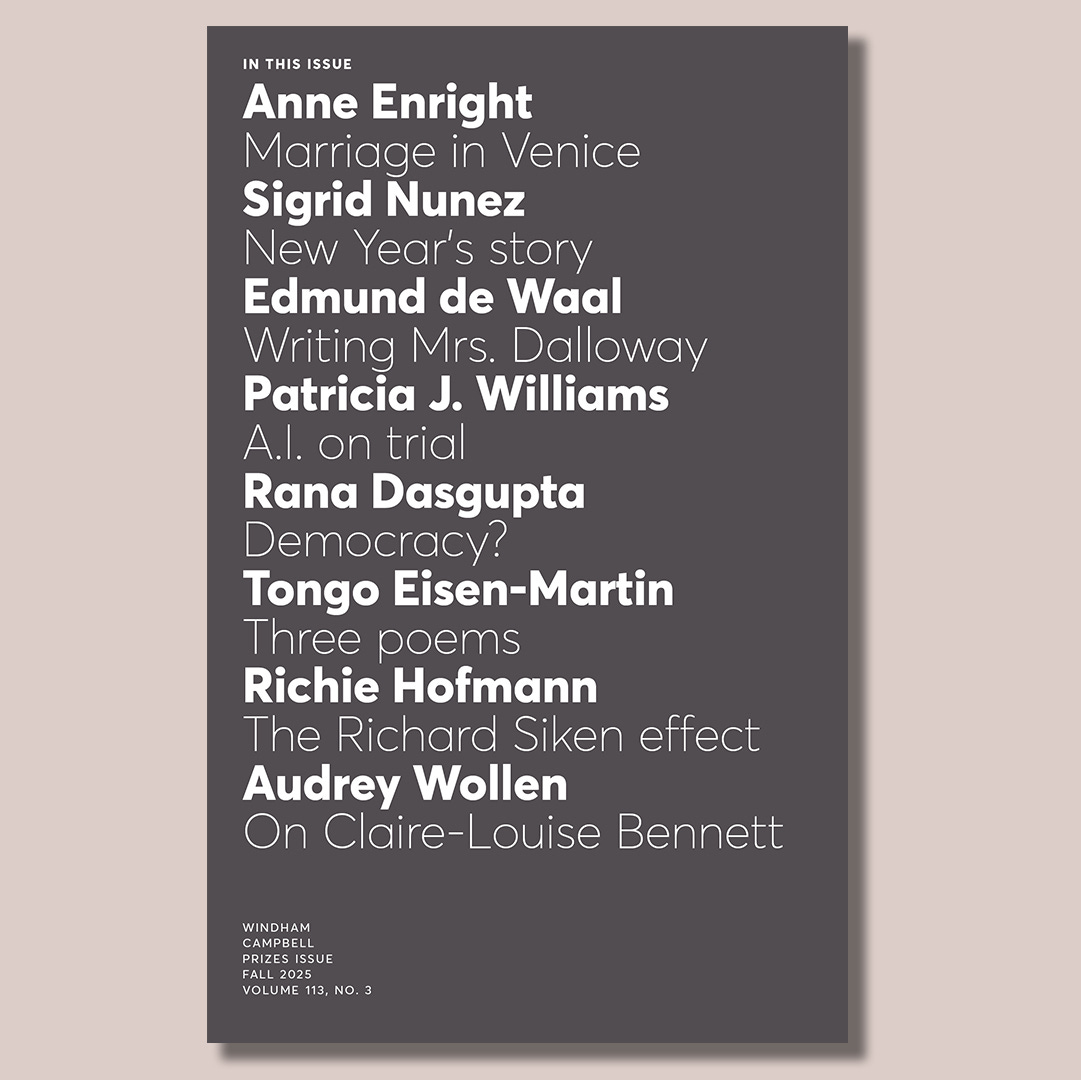

Subscription Sale: Final Days. Subscribe to The Yale Review before Tuesday, August 5 to receive our fall issue—featuring new work from Windham-Campbell prizewinners past and present, and much more—and save 20%.

Alicia Kennedy has a very nice essay on note taking practices — https://www.aliciakennedy.news/p/on-to-do-lists-and-my-notebooks

"I said I supposed he was saying that I wasn’t always right." Classic Didion.